BESTSELLERS

When I was a child, I played with superhero dolls—"Rescue Heroes"—that let me imagine tenderness and bravery at once. They weren’t just toys; they were tools for learning how to care, how to protect, how to empathize. That early sense of empathy is something I’ve carried into my work as a photographer.

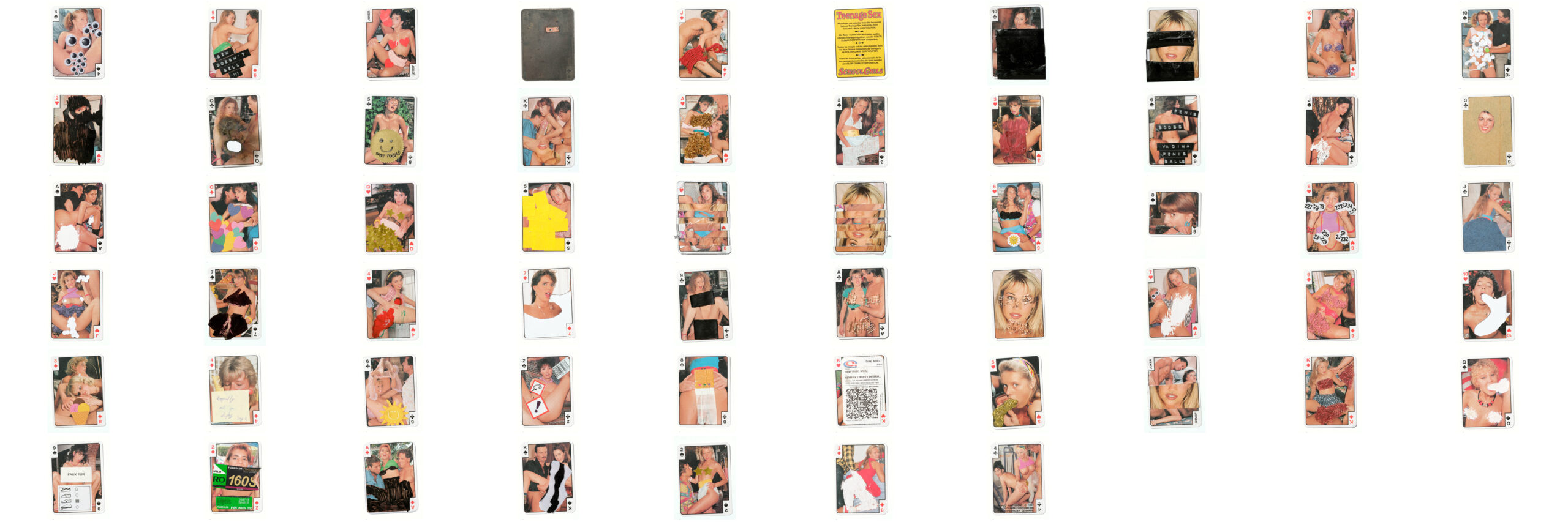

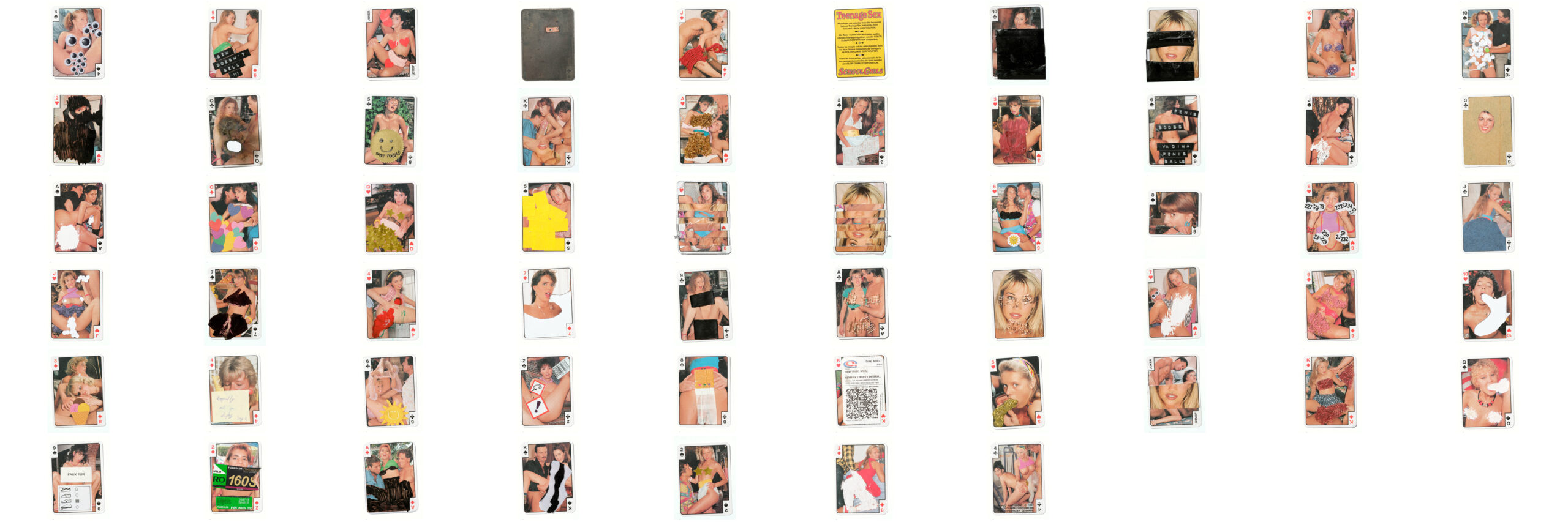

This project began with a difficult object: a deck of old playing cards from the 1990s, inherited unexpectedly from my grandmother. They had belonged to my uncle. Slipped between family photo albums, these cards featured nude images of young women—images that, as I later realized, toe an uncomfortable and inappropriate line in terms of age, consent, and cultural acceptance. When my grandmother gave them to me, she asked me to burn them. To erase them.

But I couldn't. Not because I wanted to preserve them, but because I wanted to understand them. As a male artist—and as a son, partner, and someone who hopes to raise children—I felt a responsibility to confront the culture that normalized these kinds of images, especially when aimed at boys and men. These women weren’t being celebrated—they were being commodified. Their bodies flattened into function: seduction, consumption, disposal.

I chose not to destroy the cards but to intervene. Using simple tools—nail polish, tape, white-out, household materials—I began a process of physical alteration. I scratched, covered, veiled, and peeled. Not to censor, but to reclaim. Through the act of erasure, I looked for presence. Through disruption, I sought to restore dignity.

This is not a project about nostalgia or provocation. It’s a reckoning—with masculinity, memory, and the way visual culture teaches us who is allowed to look, and who is meant to be looked at. These cards were never neutral. But perhaps, in being altered, they can begin to speak again—not as objects, but as traces of women who deserved better than the gaze they were given.

Bestsellers

When I was a child, I played with superhero dolls—"Rescue Heroes"—that let me imagine tenderness and bravery at once. They weren’t just toys; they were tools for learning how to care, how to protect, how to empathize. That early sense of empathy is something I’ve carried into my work as a photographer.

This project began with a difficult object: a deck of old playing cards from the 1990s, inherited unexpectedly from my grandmother. They had belonged to my uncle. Slipped between family photo albums, these cards featured nude images of young women—images that, as I later realized, toe an uncomfortable and inappropriate line in terms of age, consent, and cultural acceptance. When my grandmother gave them to me, she asked me to burn them. To erase them.

But I couldn't. Not because I wanted to preserve them, but because I wanted to understand them. As a male artist—and as a son, partner, and someone who hopes to raise children—I felt a responsibility to confront the culture that normalized these kinds of images, especially when aimed at boys and men. These women weren’t being celebrated—they were being commodified. Their bodies flattened into function: seduction, consumption, disposal.

I chose not to destroy the cards but to intervene. Using simple tools—nail polish, tape, white-out, household materials—I began a process of physical alteration. I scratched, covered, veiled, and peeled. Not to censor, but to reclaim. Through the act of erasure, I looked for presence. Through disruption, I sought to restore dignity.

This is not a project about nostalgia or provocation. It’s a reckoning—with masculinity, memory, and the way visual culture teaches us who is allowed to look, and who is meant to be looked at. These cards were never neutral. But perhaps, in being altered, they can begin to speak again—not as objects, but as traces of women who deserved better than the gaze they were given.